Outdated dictionaries: a chat with Dr. Geoff Lindsey about the changing pronunciations of modern English

When you’re not sure of a word’s pronunciation, where do you turn to? The dictionary? While this is a good choice, once in a while, these authoritative books may themselves also be wrong. This is because as language changes, dictionary writers may sometimes struggle to keep up with the times. What was considered “correct” 50 years ago, may be old-fashioned today, or worse, wrong! Caveat lector, indeed!

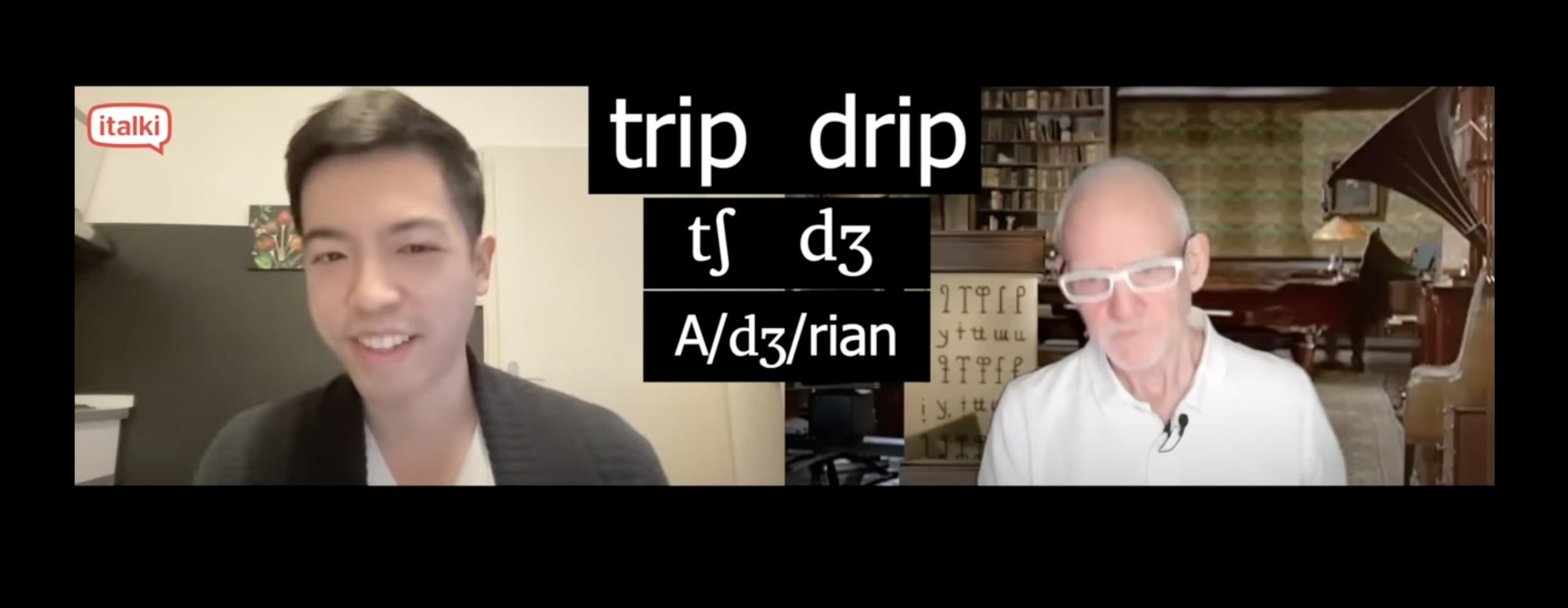

Language is always changing

This is the topic I discussed a few weeks ago with Dr. Geoff Lindsey when he interviewed me for his video on Outdated Dictionary Transcriptions of Words due to the changing pronunciations of English words. For those of you who don’t know, Dr. Geoff Lindsey is a prominent British linguist, author, and YouTube educator on the English Language. I’ve watched quite a few of his videos and my students regularly send me his videos as well. So I was quite excited when he contacted me on the iTalki, the platform I teach on and booked a lesson with me for the interview (iTalki was the sponsor of his YouTube video after all). He said he had seen my iTalki introduction video in which I spoke in seven different languages and did various accents and knew he wanted specifically me for his American accent coach (he also interviewed two British and an Australian English accent coach for his video.

Chatting with Geoff was fun. We actually chatted for over an hour on various linguistic topics and new changes in the English language. He actually made a big deal about my having taken classes with Dr. William Labov, a giant in the field of linguistics who is considered the “father of sociolinguistics”, as well as having taken classes with his wife Dr. Gillian Sankoff, while at Penn. Specifically, I had taken Dr. Labov’s class American Dialects, where we discussed the distinguishing features that differentiated dialects of American English in their respective regions, as well as the trends of change.

Out of date examples:

This is of course, what we discussed for his video as well, and here are some topics we talked about, some of which were included in the video and others that weren’t.

Noun patterns used for verbs, e.g. to IMport rather than to imPORT:

Traditionally, textbooks taught that there are certain word pairs in English where the verb is stressed at the end whereas the noun or adjective is stressed at the beginning. Increasingly, however, English speakers, particularly Americans, seem to be using the noun form for the verb. Thus, both the noun “import” and verb “to import” are now stressed on the first syllable “im-”. However, this change isn’t uniform, as other words still retain this stress pattern, such as “to reCORD” and “a REcord”.

The regularization of word structures, e.g. mischievous as misCHIEVious:

Here we discussed a common “mistake” native speakers make, pronouncing “mischievous” as if there were an “i” in the ending. I personally prefer the i-less version as it is still considered standard, so I was quite surprised when Geoff showed me that apparently people have been “misspelling” it with an -i- for a long time. It’s also a word with a unique ending as there are no other attested words ending in -vous but a bunch ending in -vious (envious, oblivious, devious, obvious) and so it’s understandable that English speakers may regularize the spelling and pronunciation to mis-CHIE-vi-ous. Other such words include “nuclear” being pronounced as “nucular” since no other English word ends in -clear /kliər/ but many do end in -(c)ular (e.g. molecular, funicular, regular, popular, etc).

Another interesting thing that I learnt was that whereas Americans pronounce “mischief” with two /ɪ/s, as in /ˈmɪstʃɪf/, Brits pronounce “chief” with an /i/ as in /ˈmɪstʃif/. This difference in vowel quality (stressed or unstressed) can sometimes be contributing factor to pronunciation changes, which brings us to our next change...

The plural of process ending in an “eeze” sound /iz/ rather than traditional /əz/

Geoff asked me about the word processes and how Americans might pronounce it. I knew about this and personally pronounce it with the regular English ending /əz/ as with “recesses”, such that the plural noun “processes” 3rd person singular verb conjugation “he processes” are pronounced identically. However I was aware that a lot of Americans pronounced it with an /iz/ ending, identical to the word “ease”. I mentioned i thought 90% of Americans pronounced it this way, but Geoff said it’s probably not that high, and subsequently American commenters in the video comment mentioned that they’d very rarely heard that pronunciation. One commenter mentioned it sounded like corporate speech, which I think is true. My having studied at UPenn which is most famous for its Wharton School of Business and therefore having had many corporate-inclined classmates, as well as my having worked for a while in the corporate world may have influenced my perception of its ubiquity.

Tr Dr affrication: pronouncing the t’s and d’s as ch’s and ‘dg’s before /r/

The last major topic that I’ll discuss in this blogpost today but not the last of the video (there are many more, so you should check it out) is the /dr/ and /tr/ sounds in newer English. While it’s spelled as “tr” and “dr”, its actual phonetic value in younger speakers of English is actually an affricate [tʃr] and [dʒr], as if you were saying “chr” and “dgr”.

While for Geoff, “tr” and “dr” feel clearly like /tr/ and /dr/, he also mentioned an anecdote about a child spelling “Storm Troopers” as “storm chroopers”, indicating that a structural, phonemic-level change, with younger speakers conceptualizing the sound of “tr” and “dr” not actually as /t/ or /d/ as all but as /tʃ/ and /dʒ/. I also shared a story from my childhood when I wondered why “dragon” was spelled with a “d” when it clearly had the same sound as the “j” in “jam”, and even wondering why my name was spelled with a “d” as “Adrian” rather than the more—I thought—accurate “Ajrian”.

One thing that was identical for both of us, is that we both taught our accent modification students to pronounce these sequences “tr” and “dr” as if the “t” were “ch” and the “d” were “dg” because non-native English language students tended to otherwise pronounce these sequences with a kind of a trilled R; pronouncing it with the affricates “ch” /tʃ/ and “dg” /dʒ/ resulted in the learners producing a MUCH more native-sounding sound.

So does this mean you shouldn’t trust dictionaries?

Well no, dictionaries are still a good source to help you understand what sounds should go where. Oftentimes, students’ mispronunciation of an English word is not because they cannot pronounce the sound but that they think that it’s a completely different sound, e.g. with students thinking that “only” is basically “on” /ɑn/ + “lee” /li/, resulting in *[ɑnli], whereas in fact it is phonetically “own” /oʊn/ and “lee” /li/ as in /oʊnli/. For situations like this, dictionaries will by and large help clarify which sounds you should use.

However, once in a while dictionaries may have out-of-date transcriptions and it’s always helpful to consult real life materials such as those found on YouGlish.com. Asking accent coaches and English teachers also helps you get the more up-to-date pronunciations. I provide such instruction in my live training sessions or my video courses, such as Complete English Pronunciation, which contains lessons on all the sounds of English, helping you speak clearly, confidently, and comprehensibly. Also, you can sign up to my free email mini course that will provide free materials and teach you the basics to get started improving your English pronunciation and American accent